Festival de ‘Usual Suspects’: Basic Instinct (1992) de Paul Verhoeven

April 29, 2016 § Leave a comment

For Halloween 2015, I produced a short video tribute to giallo cinema for online film publication 4:3. Had I seen this Verhoeven picture beforehand, I would almost certainly have included any one of several moments that seem lifted from if not merely inspired by that Italian horror/thriller sub genre. Even the pulpy plot, which finds San Francisco detective Nick “Nicky” Curran (Michael Douglas) becoming increasingly entangled with a sexily icy/icily sexy novelist who may or may not be translating her fictional homicides into actual homicides, is somewhat reminiscent of Dario Argento’s Tenebre. But ultimately, more than it is a not-so-sly tribute to Hitchcock’s Vertigo (that alabaster outfit!) or giallo or what have you, Basic Instinct is a Paul Verhoeven film through and through, unabashedly unshy and impeccably crafted. Perhaps it has to do with his pre-cinema background in the world of mathematics and physics, but there is something thrillingly calculated about Verhoeven’s ability to construct what are – in my opinion – first-rate mainstream entertainments that end up becoming cult classics due to misappreciation. Then again, perhaps it’s this very calculatedness that leads to accusations of ‘superficiality’ and ‘hollowness,’ rendering his films contentious, utterly working for some while utterly not working for others. Well, I guess this cannot be helped. As for Sharon Stone in her role as paperback-writing titillator Catherine Tramell, it’s a travesty that her vagina’s infamous split-second cameo has upstaged what is a perfectly calibrated performance, in the context of the film and its tonal fabric, that is. Which is how every performance should be judged: In context.

Festival de ‘Usual Suspects’: Kes (1969) de Ken Loach

April 26, 2016 § Leave a comment

Maybe the reason for Ken Loach’s countless appearances at Cannes lies somewhere in his outstanding 1969 debut feature, Kes, in between the groggy naturalism of the performances and the wintry lyricism of the images Loach and cinematographer Chris Menges captured in South Yorkshire, a marriage of pastoral and industrial: “Make a film like this and you’re always welcome at Cannes,” where Kes premiered in the Critics Week sidebar. Named for the gorgeous falcon stolen from its nest as a chick, trained and utterly adored by scrawny adolescent protagonist Billy Casper (David Bradley in a one-hit-wonder role, it seems), Kes looks, feels and moves like 60s British kitchen-sink realism seduced somewhat by the jazzy swagger of the French New Wave. Without a doubt, when people speak of Kes, Truffaut’s The 400 Blows must be dancing around within the same breath, and for good reason. Both films feature young working class lads (or garçons) whose hearts are good and decent but whose minds are not easily corralled and appeased by the confines of home and school. But where rascally Antoine Doinel enacts his rebellion is his own small prison-landing ways, the sweeter Billy retreats to nature somewhat, finding a kind of feral kinship with a bird he sees more as a peer than as a pet and, by way of this, finding an impressive sense of purpose too. An arguable if not undisputable granddaddy to the types of rough, humane films made by the last two competition entrants (Arnold and the Dardennes), Kes is rightfully heralded as a pinnacle of social realist cinema, one which Loach has barely strayed from if at all. With vernacular so thick and specific that I shamefully conceded to using subtitles, Billy and his fellow characters conjure a hardscrabble world in which hope sits like a gem within a vast ore, glinting every once in a while to distract from despair. Kes is landmark stuff.

Festival de ‘Usual Suspects’: Milk (1998) de Andrea Arnold

April 20, 2016 § Leave a comment

Eight years before her Cannes Jury Prize-winning feature debut Red Road (2006) and a mere five before her Oscar-winning short film Wasp (2003), Andrea Arnold transitioned from actor to director with this ten minute tale of Hetty, a woman trying – and perhaps failing – to handle the blood-stained tragedy of a stillborn child. It’s always fascinating to explore the work of a filmmaker who would eventually develop a more unique signature style, and Milk is one such work, replete with fixed cameras shots!, dollies! And dreamy focus-pulls! It feels like an early work, yet the most fascinating aspect of this short is – hindsight granted – the way in which it prefigures a future auteur in its tonal and formal shifts. What begins with respectfully composed images of comfortable domesticity ends with a moment of raw, feral honesty, contained within tight and intimate framing. Milk almost preempts Arnold’s adoption of handheld naturalism, an approach very similar to the Dardennes’ in fact. Perhaps the one thing which clearly declares itself from the get-go is Arnold’s deft hand with her performers (having been a performer herself, one could assume), able to nudge them into a place of utter vulnerability and, in doing so, to tease out moments of unadorned humanity, always slightly askew. On this front, Arnold has only gotten better with time.

MILK (1998) from Tope Ogundare on Vimeo.

Festival de ‘Usual Suspects’: Le Fils (2002) de Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne

April 20, 2016 § Leave a comment

I knew there was a good reason for my being quietly unconvinced when praise was being heaped upon Laszlo Nemes for his ‘groundbreaking’ visual approach to Son of Saul with it’s heavy reliance on tight close-up shots hovering within mere feet of the protagonist’s head and shoulders. Having finally seen that film and having now seen Le Fils, I realise that the reason for my skepticism was ‘the Dardennes,’ granted – of course – that Nemes’ use of focus and depth-of-field remains unique and laudable. Either way, watching the Belgian brothers’ 2002 slice of unembellished realism and thinking back to their sophomore effort Rosetta (their first Palme d’Or clincher), I am struck by the commitment and intensity with which – in these two pictures, in particular – they consolidate this mode of extreme spatial intimacy, their camera breaching their characters’ ‘safe spaces’ and maintaining this intrusion for extended periods in a way that seems initially claustrophobic and coarse, but which somehow leads to unprecedented emotional combustion and a strange kind of narrative purity. And while I may ultimately prefer the slightly more refined fairy-tale austerity of the Dardennes’ more recent work, Le Fils is perhaps the best example of their ability to strip a somewhat dubious premise of all sensationalism, only to gradually infuse the spare remnants with dramatic doses of humanity. In their hands, this unassuming story of a woodwork instructor (Olivier Gourmet) whose new apprentice happens to be his son’s killer is a gently unsettling tug of war between forgiveness and vengeance; between moving on and hanging on.

Festival de ‘Usual Suspects’: Zelig (1983) de Woody Allen

April 18, 2016 § Leave a comment

This unofficial festival’s official opener is a shocking reminder of the artistic powerhouse that Woody Allen once was. Even his more acclaimed contemporary output (Midnight in Paris, Blue Jasmine etc.) registers as downright comatose in comparison with this mockumentary that practically bursts at the seams with borderline offensive irreverence and giddy wit.

A picture that I, due to either misunderstanding on my part or misinformation on the part of another, believed to be a mockumentary about a time traveller of sorts, Zelig boasts a central conceit that is equally as fantastical as time travel but far more original and pregnant with comic potential. Seemingly driven by an intense need to ‘fit in’, Depression Era schmuck Leonard Zelig (Woody Allen) has developed the chameleonic ability to blend into his social surroundings so much so that he morphs without cue, racially, anthropometrically, intellectually, what have you; though it is interesting that his gift/curse lacks a transgendering function.

What follows is a fleet-footed account of how psychiatrist Dr. Eudora Fletcher (a characteristically willowy Mia Farrow) pin-points the psychic nature of Leonard Zelig’s shape-shifting malady and thus proceeds to cure him by way of psychoanalysis and – eventually – unwitting romance, two slam-dunk Allen hallmarks.

After over a decade of mild-mannered ensemble comedies, one is in danger of forgetting that Allen, at his peak, was not simply the high priest of neurotic, East Coast intellectual humour, but a relentless formal innovator. From the use of double exposure and subtitles in Annie Hall to the mind-boggling blend of staged and archival footage on show in Zelig (achieved via blue screen), Allen’s brand of dramatic comedy has had a surprising impact on cinematic form over the decades, in addition to its fearless marrying of the highbrow and the low.

Of course, one cannot or should not expect that the creative restlessness of a middle-aged comic will necessarily continue into his old age. Surely enough, Allen, now 80, sports a face which was once compellingly sardonic in its stoniness but which now reeks of boredom and complacency; or perhaps just plain-old burnout. In many ways he is entitled to this, what with his filmographic output. But I also reserve the right to mourn the loss of the Woody Allen that cinema once had, not that his films will be lost in a hurry.

For the moment, the twenty upcoming films In Competition should count themselves lucky that Zelig is Out of Competition. I certainly count myself lucky for having finally seen it.

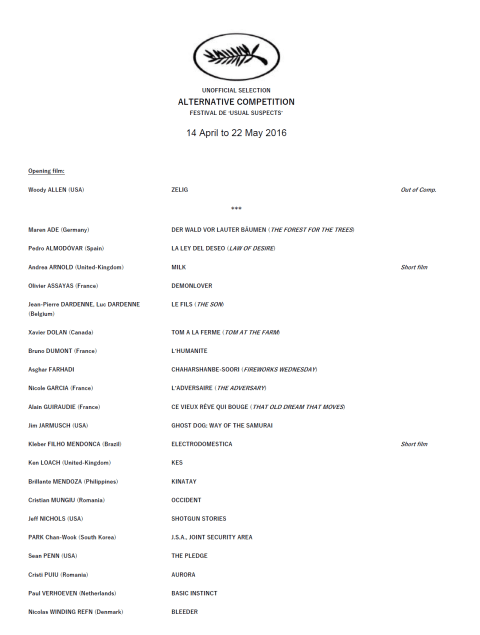

Festival de ‘Usual Suspects’

April 16, 2016 § Leave a comment

My maiden post on this very blog was a simultaneous defence of the sovereignty of the Cannes Film Festival programmers (headed by director Thierry Fremaux) and an attack on their predictability when it comes to selecting films to screen in Competition.

Well, the Official Selection for the 69th Cannes Film Festival has finally been announced. And, once again, Fremaux finds himself defending not only the festival’s apparent unwillingness to champion female directors (whether emerging or established ), but refuting suggestions that there is a certain curatorial inertia plaguing this bastion of international ‘auteur’ cinema; one which will see Ken Loach (an admittedly fine film-maker) returning to the Riviera with his 17th feature film, and his 13th in Main Competition. Whatever one’s stance on this snowballing gripe, being a Cannes regular is one thing, enjoying tenure is another; and enjoy it Loach certainly does.

In response to accusations that this year’s competition features nothing more than the ‘usual suspects,’ Fremaux reminds us that directors Maren Ade and Kleber Filho Mendonca are both newcomers to Cannes, or at the very least, to the Main Competition slate. Yet, both film-makers are well known and well respected quantities on the backs of their last films (Alle Anderen and Neighbouring Sounds, respectively), and could in some ways represent the new guard of Cannes stalwarts, joined by Alain Guiraudie who will make his Competition début after his successful stint in Un Certain Regard several years ago. But so as not be be overly presumptuous and cynical, the presence of these three directors and their new work is relatively refreshing in the face of the other 17 entrants, all of whom have previously competed for the Palme d’Or.

But once the sickly feeling that Cannes is deeply conservative wears off, I am reminded, with a thud, that these so-called ‘usual suspects’ represent a sizeable chunk of cinema that I have not yet seen. Bar Andrea Arnold, whose feature filmography I am very much acquainted with, I cannot claim any degree of familiarity with the directorial efforts of Nicole Garcia, Brillante Mendoza, Sean Penn and Xavier Dolan, and this has resulted in my decision to undertake a personal marathon of sorts which I have considered for several years.

Prior to the the opening of the Festival du Cannes on May 11th, I will set out to view one film from each of the 20 directors in Main Competition this year, one film that I have not yet seen. In keeping with the Cannes festival website, I may or may not produce ‘Dailies,’ which will most likely take the form of a capsule review. At the end of it all, I the jury will confer my own awards, from the Palme d’Or to the Technical Grand Prize (should I be so inclined).

Of course, I will commence my marathon by viewing Woody Allen’s Zelig (1983).

What follows is my own Competition line-up which has been revised (as of May 9th) to reflect the inclusion of Asghar Farhadi’s new film Forushande (The Salesman) in this year’s Cannes Competition. The announcement was made on April 22nd.

(click to enlarge)

Metamorphoscissors: a video essay

April 4, 2016 § Leave a comment

Halfway through the climactic sequence of Jerry Lewis’ 1963 picture The Nutty Professor, I was slapped in the face with a realisation that made me press ‘pause.’ A physical transformation was taking place on-screen – that of charismatic asshole Buddy Love as he reverts back to sweet but bumbling Professor Julius Kelp – and it was being orchestrated by way of simple cuts. Lewis and editor John Woodcock were able to create – at least for me – a seemingly seamless illusion by flipping back and forth between Love/Kelp and his dumbstruck college audience, patiently introducing fairly obvious but functionally subtle physical changes with each cut.

The very first transformation sequence, in which chemist Julius Kelp – with the help of a comically colourful brew – turns into his dapper and cocky alter ego, is even more perplexing in its effectiveness. Akin to a scene from a German Expressionist silent picture, Kelp’s maiden transformation eschews any attempts at a ‘realistic’ portrayal of physical reconfiguration, aiming instead for something more – well – expressive. Achieved once again through straightforward cutting though much swifter, the sequence’s focus on the mayhem and violence of the process, paired with comically garish staging and makeup, places it somewhere in the realm of horror-comedy. It’s a moment that’s more invested in relaying the emotional toll of despising oneself to the point of self-harm than it is in attaining some kind of visual verisimilitude. These mild horror elements most certainly taint the apparent improvement in Kelp’s physical and social status, a sly comment on the eventual end product of the transformation. Buddy Love may not look like a monster, but in many ways he is, at least according to the process by which he is given birth.

These two transformation sequences seem to occupy a space between the artfully implied metamorphoses found in old-school, low-budget pictures like Cat People (1942) and more visually graphic practices, from the prosthetic contortions of mid-to-late 80’s horror, to the digital deceptions of nowadays. Of course, each of these approaches produces distinct effects, and my decision to explore the use of cuts in The Nutty Professor by visually de-constructing the two aforementioned sequences is a matter of curiosity not preferential advocacy. In fact, this exercise really highlights the vast visual fissures that Lewis and Woodcock manage to breach editorially so as to achieve a sense of seamlessness, in turn deepening my appreciation for the overall effectiveness of these moments as they play on-screen in ‘real time’, or rather ‘film time.’

The ups and downs of modern Africanity: a video essay

November 16, 2015 § Leave a comment

Is the persisting relevance of a forty-year-old satirical film a testament to the satirist’s socio-political foresight, a vindication of his jokey pessimism, or an indictment of a nation at large? It turns out that viewing Senegalese auteur Ousmane Sembene’s Xala (1975) in a contemporary context provides ample evidence in favour of all three.

At the risk of being overly speculative, it is not unreasonable to posit that Sembene busied himself crafting politically-charged art in the hopes of encouraging the kind of cultural and national self-awareness necessary for social integrity and progressiveness, particularly in the wake of newly won freedom from colonial rule (1960 onwards in the case of Sembene’s native Senegal). Whether or not he intended for his work to be representative of extra-Senegalese Africa is beyond my knowledge, though its influence on sub-Saharan cinema in general is quite simply undeniable.

Suppose then that Sembene, in 2006, happened to sit down and watch Abderrahmane Sissako’s impassioned Bamako, an allegorical portrait of a Malian town whose residents are caught between continued colonial exploitation and post-colonial mismanagement. It’s hard to imagine him taking even perverse pleasure in the realisation that his decades-old films, Xala in particular, have proven to be somewhat prophetic, almost to the point of seeming like a curse. As I mentioned in my piece on Bamako, Sissako simultaneously celebrates and bemoans the paradoxical mess that is contemporary Africa, suggesting that somewhere in this muck lies the source and solution of the continent’s woes, fiscal and otherwise. Strangely enough, ‘contemporary’ in this context spans a good thirty years, all the way back to Xala, if not further.

The pleasure (and pain) of expression: an interview with Benny Safdie

October 12, 2015 § Leave a comment

Having been tasked with writing a feature article for Melbourne International Film Festival – as part of my previously mentioned involvement in the 2015 edition of Critics Campus – I initiated the process by dutifully poring over my personalised viewing schedule in the hope that random groupings of films would serendipitously reveal a common theme worthy of investigation or mansplanation. Well, a theme did not present itself so much as the sobering realisation that, of all the screenings I had booked on my festival pass, approximately zero were documentaries.

This bias in favour of fiction – on screen and on the page – seemed tailor-made for a confessional self-interrogation in which I challenged my own supposed aversion to non-fiction filmmaking. Yet, on further reflection it became obvious that this aversion was not directed at documentary (as a branch of cinema per se) as much as it was at a seeming majority of documentary films that are convinced of their own factuality, to the point of formal malaise; or rather, films that fail to appreciate the inherent subjectivity of the cinematic medium.

While this stance did not (and does not) in any way justify the inanity of depriving oneself of outstanding work in protest of the presumptuous and formulaic (equally true of fiction films), it possessed sufficient ideological fuel behind it to warrant further inquiry, not least because the Safdie brothers were guests of MIFF 2015 on account of their newest film Heaven Knows What being in the official selection as part of a retrospective of their work to date.

Why the Safdie brothers? Well, Josh and Benny Safdie are two New York filmmakers whose work drifts incessantly between the realms of the actual and the imaginary. Heaven Knows What is a fictionalised recounting of an actual individual’s experiences, with said individual (Arielle Holmes) playing a fictionalised version of herself. However overstated the novelty of this may be in the press and publicity spheres, especially as the film travels the festival circuit and rolls out globally, it is an undeniably uncommon approach which knowingly draws attention to the emotional and expressive purpose of storytelling and of cinema, for both the performer and the audience. Interestingly, the film’s screenplay is adapted from Holmes’ self-authored memoir which begs the question: where did the fictionalising actually begin? Either way, John and Benny Safdie have been melding fiction and fact long before Heaven Knows What. Their previous ‘fiction’ feature Daddy Longlegs aka Go Get Some Rosemary similarly draws on the experiences of individuals who in fact existed (and still do exist), while their feature debut The Pleasure of Being Robbed utilises the streets of New York City (and possibly Boston) in a way that is utterly non-staged and which – as a result – frankly borders on what one might call documentary. Oddly enough, the blending of the fictional and the real somehow enhances the drama of the former while feeding into the curious thrill of seeing factual ‘reality’ projected onscreen. And of course, one can’t forget the Safdies’ documentary feature Lenny Cooke which actively challenges the idea that the documentary form is or should be subject to certain expressive limitations. In short, these filmmakers were the perfect guys with whom to discuss fact, fiction, and filmmaking, and where these three intersect.

Needless to say, I was lucky enough to speak with Benny Safdie on August 1st. My feature article for MIFF Critics Campus was fashioned around a heavily edited and truncated version of this interview, but what follows is the full transcript, excluding my personal introduction to Benny which was essentially a compressed version of this very preamble. Enjoy.

Tope Ogundare: You mentioned hybrid films in an interview with The Dissolve (the sadly now defunct online publication). Does that mean you make a distinction between documentaries and fiction films?

Benny Safdie: Well, it’s difficult because the thing is…Heaven Knows What, I guess, would be kind of the ultimate hybrid film. We’re taking a real person and having her re-enact parts of her past. In this case, it’s not a hundred percent fact, but it rings emotionally true, you know? I think that’s the most important thing. Did you see our documentary Lenny Cooke?

Actually, I have seen it. It’s great.

That’s another instance where there are a lot of things that are constructed and changed to get at the overall truth. [Werner] Herzog called it the ‘ecstatic truth.’ Josh [Safdie] says ‘you always have to lie to tell the truth.’ That’s true, you know? Sometimes real life isn’t as interesting as it seems when you experience it, so, if something happened to me and I tell you exactly what happened to me, you might think, ‘oh, that’s boring.’ But if I change it and I make it more exciting at certain parts and I lie, you will feel exactly what I felt when I went through it. That’s kind of blurring the lines of reality and truth, but at the same time it’s making you feel what I felt, and that to me is real. I think the main issue with documentary films is…there’s this kind of – um – false sense of…

Objectivity?

Well, yeah. Objectivity’s such an important topic to breach. The only thing that’s objective by nature is a security camera. If I see a security camera that’s subjective, it makes me think that something bad’s going to happen. I think that maybe the documentaries that come closest to objectivity are those on The History Channel, or some random thing about the government playing on the television. Or if there’s no feeling and no emotion and it’s just a straight document of a certain topic. That’s what most people think of when they think ‘documentary’. But – like – some of the best documentaries by Frederick Wiseman or the Maysles brothers, or D.A. Pennebaker…there’s a lot of work going into those to make them seem effortless. But that work is filmmaking, and I think when you see something….when you make a documentary that transcends recording, it just becomes a movie, and a movie is a movie…is a movie. So, I don’t like the distinction between documentaries and fiction films because it kind of diminishes what some documentaries have the ability to do. There are some documentaries where you’re just watching them to get information and audiences go in with the mindset of ‘I’m going to learn something about this.’ But then you see Senna, and it’s a completely cinematic experience. It’s this beautiful use of archival footage and there’s manipulation going on, but at the same time it’s telling you a story, and it’s telling you a story in the best way that it can. That’s what a movie is.

You mentioned that the documentary community didn’t really embrace Lenny Cooke.

(Benny Safdie chuckles)

…that they thought you were doing something wrong. What exactly could you have done to make Lenny Cooke more respectable or appreciated?

It felt like there was some sort of documentary mafia. Granted, making that film was a lot of learning for us. We worked with one editor but it didn’t work out and I had to take over and edit the film, because I knew where it needed to go, but the main issue was that there was a lot of manipulation with the footage, and there was a lot of manipulating of the timeline. And these are all things that you just don’t do in documentaries. You do that in fiction film because you can, and it gave me nightmares personally when I was going in and changing these things. But it wasn’t affecting how you looked at Lenny in any way. It was more about getting you to feel from his point of view. But the elements I was manipulating are considered the law in the documentary world, and if you’re treating them in this way, they say it’s a slippery slope. But it’s this kind of combination of journalism and documentary that kind of makes it difficult.

Lenny Cooke didn’t get into any documentary festivals. It didn’t get any respect as a documentary, and it was strange to me because we felt we really did justice to Lenny and his story, which had rarely been told. It’s reflected in how people respond to it, but it had to get out there in a different way, and it had to do it outside of the documentary community. There is this tendency to say ‘okay, you need to do things in a documentary responsibly.’ This kind of leads to a different branch of movies. I think that the perfect example is Citizenfour. I went into that movie saying ‘okay, this is going to be a standard documentary about what [Edward Snowden] did. But watching it and realising that it’s the direct experience of this guy who’s doing something that he’s frightened to do, and that the film is a once in a lifetime chance to see this kind of thing first-hand…and watching the way [director Laura Poitras] treated the subject, and the way she edited the film and worked the material…it was a movie. We’re caught up in what he was doing, but at the same time it gives you an insight into what was happening in the real world. Plus, the movie had an effect on actual policy. But that was because it wasn’t something you could just write it off as ‘just some left wing propaganda.’

She apparently hired an editor (Mathilde Bonnefoy) who had previously worked on thrillers (i.e. Run, Lola, Run and The International). She was clearly trying to utilise that sort of approach even though she was telling a factual story.

Of course. The fact is we were fiction filmmakers [when beginning work on Lenny Cooke]. We didn’t expect to ever make a documentary, and when Adam Shopkorn the producer approached us, we thought: ‘well, is there something in this with which we can express ourselves, or at least really express some ideas?’ And there was. It was interesting because we had to figure out how we were going to take this all camera footage that he had captured over three weeks and turn it into a collection of scenes, and create a cinematic experience with it. But once we realised we could do that, it led to a lot of interesting choices, for example, with the [time travel] special effect where he talks to himself at the end.

Was that one of the big issues? Is that one of the things that people didn’t like? Because it’s one of the best parts of the movie.

A lot of people said, ‘well, that’s not okay.’ A lot of people were saying, ‘we already knew that; you don’t need to do something like that to make the point.’ But you do, you know?! He needed it for himself, and we needed it for the film, to take it to the next level; to really bring it to this new place. And it was important. But it was something that people thought wasn’t okay. That it was something you don’t do in a documentary. We were just operating under the principle of ‘how do we best tell this story?’

The BFI (British Film Institute) came out with this list of 50 documentaries that a lot of documentarians and film writers/thinkers chose as pinnacles of the form and, looking through the list, so many of them are actually very interested in playing with form. They weren’t simply intimations of objective fact. You’ve got Man with a Movie Camera at number one…and that is really an essay movie. You’ve got Shoah, you’ve got Night and Fog and The Thin Blue Line. It’s interesting that a lot of filmmakers and critics do appreciate the fact that the best documentaries are not that different from fiction in the way that their made. They’re just cinema, as you’ve said. So why is there still a sense that documentaries are meant or expected to be an objective record of reality, which is not even possible with cinema?

It’s weird, because some of the best documentaries, all the way back the 60s – those by Pennebaker, the Maysles, Wiseman – what they’re doing is manipulating reality. They’re making things up with the editing and yes they are celebrated as the greatest documentarians. But I don’t know why there is a double standard. There are some people who are doing it now, like Josh Oppenheimer with The Act of Killing. He’s kind of playing with the form in a way that is very interesting, and doing things that are definitely not okay in a documentary in the normal sense: the aggressive nature of [Oppenheimer’s process] on this guy, of getting him to repent. It’s insane what [Oppenheimer’s] doing…the re-enactments. I think that Errol Morris does it too, and I think it’s interesting. I can’t really speak for other people; I can only speak for what I am seeing coming out, but maybe there’s this ability to appreciate that these daring documentaries are great and that the filmmakers involved took risks. But there is this fear. It doesn’t matter if you change things or make things up in a fiction film. But if you do that in a documentary, some people are going to point this out and say you’re being irresponsible; that you’re not being responsible to the subject. But…I don’t know. I don’t know why there aren’t more movies made like that.

At the same time, each movie should be its own thing. A filmmaker could take cues from those and learn from them, not that they should copy anything…but it is funny that there’s a list like [the aforementioned BFI list] and it isn’t being reflected in what’s being put out. I think it might just be that there is this kind of police force out there that’s always out to get you, and if you’re making a documentary film you’re not as protected by fiction. In defence of the people making these documentaries, they have to abide by certain rules and they kind of have to play with or bend the lines a little bit but not too far so their work is not completely disregarded by this community that needs to be there to support that film. So…in that sense, I can understand it. But it’s definitely much easier for fiction filmmaker to do whatever the hell they want: make shit up, change things, and think: ‘I’m getting at something great here and it’s emotionally true, but I don’t have to be entirely true to the facts.’ I guess in a documentary you have to be true to the facts to a certain extent.

It all depends on the function though. If the function of the documentary is to get at the ‘ecstatic truth’ as opposed to the unadulterated fact, then does it matter if you twist things?

I completely agree with you. [Werner] Herzog was 100% right. His documentaries are so weird and so strange; what he’s doing with the characters, pushing them and interviewing them and asking them piercing questions. He’s definitely doing things that may not be okay. But again, I think there are movies now being made by Laura Poitras and Josh Oppenheimer and [Asif Kapadia’s] Senna documentary – you know – that completely throw out the formula of having to show talking heads or that only use archival footage.

And then there’s the Marlon Brando doc (Listen to Me Marlon) and the Kurt Cobain one (Montage of Heck) which use those two guys’ own personal material.

Yeah. And there was one about Phil Spector, The Agony and The Ecstasy of Phil Spector. There’s now a kind of movement growing where filmmakers say, ‘okay, we can relax these guidelines a little bit;’ guidelines that are more front and centre when you’re doing something involving politics, which you kind of have to respect. Which is why I was so surprised by Citizenfour. But even with that, you have to respect a certain code of journalistic integrity because you’re not that different from the news, in that sense. Either that or you’re telling the story of an athlete…or the story of a scientist, like Herzog did with The White Diamond. You have a little more manoeuvrability and the some freedom to try and tell a story without people jumping on your back, saying, ‘oh, you made that up, or you changed that!’ What I’m saying is: if Laura Poitras had changed the way that the Snowden saga occurred in a way that was egregious, people would have pushed against it by saying that it’s liberal propaganda. So it’s a very slippery slope and I don’t quite understand it. But I will say that my experience with Lenny Cooke, being a fiction filmmaker diving into documentary, was that the film wasn’t accepted partly because we were coming at it from a fiction standpoint. It was – like –, ‘hey, get back in line!’ It was weird.

Maybe there’s a fundamental misunderstanding of the medium, because the medium is the same. Cinema is what you use for both fiction and documentary, and cinema’s inherently subjective. Even Wiseman: when he places a camera, he could place it in about a zillion different angles, but he chooses one or a couple. Why that one? Why those ones?

If you look at [Frederick Wiseman’s] High School, there’s that footage of the old principal walking through the halls. And then he looks into a window and the movie cuts to the audio of some kids singing ‘Simple Simon,’ and it implies that maybe he’s a pervert and he’s going and looking at these girls, looking at them work out. But he’s clearly not that kind of guy. But it’s an amazing moment in the film.

Do you think it’s irresponsible? This moment?

Well, it’s completely irresponsible, but it’s fine. It’s fine, you know. That guy isn’t doing that…what he’s looking at primarily isn’t those girls, but it works for the moment. I think at some point you have to step back and say, ‘I’m also making a movie here’. But it’s not all documentaries that take such liberties; it’s some documentaries.

Maybe this principal is not a pervert, but the movie’s called High School and it’s not necessarily about one particular high school. It’s about all high schools. This kind of behaviour could be true in some places. The scene is encapsulating everything in one moment.

There was actually a documentary about a Canadian high school called Guidelines.

I’ve never heard of it.

It’s a great movie in the sense that it’s at one school and understands what the kids are going through. It stays with some of them as they’re getting in trouble in principal’s office. You don’t ever see the teacher. You’re just seeing these kids coming up with these lies. At one point the girls have to explain themselves. The teacher says ‘okay, so you didn’t follow her up the stairs and you didn’t go into the bathroom and attack her,’ and one of the girls is like, ‘no.’

‘Then why did you go upstairs?’

‘Well, I wanted to go and see if she was there.’

‘That’s not following?’

She says, ‘no, I was looking for her.’

‘And when you found out she was there…?’

‘I went and smacked her.’ Which is a really weird bending of the truth. But seeing a kid come up with that, and allowing us to see what happens is incredible. Look, I think documentary is going in a direction where, maybe one day, things will be more relaxed. Our experience with Lenny Cooke was that we were these fiction guys coming along and treading on the documentarians’ territory and it backfired a little bit, in the sense that it didn’t get into any film festivals. I don’t think it got into one.

It didn’t even get into True/False [Film Festival]?

No it did not. But Heaven Knows What got into True/False, which is incredible. But then again, maybe because it can be said that it’s very clearly a fiction film. The biggest testament [to Lenny Cooke] is that Lenny sat down and watched the documentary. And then he gave us the biggest hug and was like, ‘that’s it. That’s it!” He’d never seen something that expressed his feelings and his emotions, and he felt the movie did that, you know?

Well then I guess the movie’s a success.

That tells me that we did our job. And people to this day watch it because they want to avoid the steps that he took. And whenever I’m on Twitter, some person will say ‘it’s Monday, gotta watch Lenny Cooke.’ It’s like they’re watching it to prepare themselves for the week. They’ve watched it 30 times; I can’t believe it.

I really have to ask about Heaven Knows What. Did you ever think about making it as a ‘straight up documentary’?

No. The reason we didn’t was because her stories and her life was interesting – the way she wrote them, she had a very unique perspective –, but, like I said earlier, there were certain parts of it that just wouldn’t translate to film. I think a perfect example is when she wrote: ‘Ilya came over, took my phone, saw it was Mike and broke it into a million pieces.’ When you throw a cell-phone on the street – and we shot it that way – it breaks, but it doesn’t break into a million pieces. But she thought it broke into a million pieces. [Co-writer/co-editor] Ronny Bronstein was like, ‘look, the cell-phone should fucking explode – like – into a firework. We shoot a firework and that’ll be the cell-phone.’ And the end result is so unrealistic and so ridiculous, but it fits in that moment. Initially, we threw the phone on the ground and it just wasn’t working. Plus, I think that, from the beginning, we knew we wanted to make a fiction film with her story as the basis. We didn’t want go and just set the camera down and observe these people, you know? We wanted to work with them to express something, and I think that can only happen, in this case, with a fiction film. It wouldn’t have been as powerful as a documentary. We wouldn’t have gotten to the heights that we did.

That’s an interesting point. Because, if you want to present the facts of her life, then you would be obliged to show the phone being thrown to the ground and that would be the truth of the matter. But you were chasing the emotionality of the moment; you were chasing the subjective aspect of it, which actually makes more sense. So, I guess the other question would be: did Arielle in any way mention having gained any new insights into her own experience by way of playing a fictionalised version of herself?

Yes! The thing is, at times she said to us, ‘this isn’t how it happened. I didn’t do it this way.’ And we’d said, ‘no. But if you want people to feel how you felt, we need to shoot it this way. You need to change it.’ And that gave her insight into the process. We weren’t making a documentary about the present. We had to recreate, because these were things that had already happened to her. Right off the bat, we knew we couldn’t do a documentary. I mean, sure, you can have recreations and voiceover, which is fine; but I think in this case this was how the movie had to be made. You could argue that every movie is a documentary, because it’s documenting something, you know. Making Jurassic Park is a documentary of how everybody felt in that moment.

We value acting as being this approximation of the real. So if you’re approximating or reaching the real in acting, and in performance, and in everything else, then what are you shooting? Are you shooting fiction or the real thing?

I think that the distinction really has to do with whether you’re making a movie or a documentary, and I think improperly so. It’s like, ‘oh, what did you see?’

‘Oh, I just saw a documentary.’

I don’t know how many times I’ve heard that. It’s a shame. It’s depressing. Because a documentary could be just as powerful. It’s like there are two different things. Either you’re using real to make a movie, or you’re using fake to make a movie. That’s the difference. And, in Heaven Knows What, we were using fake based on real and it blurs the line. Arielle’s not playing herself. She’s playing a fictionalised version of herself, re-enacting moments of her life. That makes it a little more unclear. There are a lot of movies that have done this. Shirley Clarke: she made a lot of strange hybrid films that are beautiful. The Iranians were making a lot of films in the 1990s that were blending reality and fiction.

Like Close-Up.

Exactly. We’ve seen that movie many times, and we’ve been – like – ‘holy shit!’ You’re taking this guy who did something and having him play this part. It’s so funny: we had it in our heads while making Heaven Knows What. It’s funny how such films are out there, and that there’s a desire to make them. But it’s essentially about how human beings express themselves. It’s an interesting topic. We took a class in college with this guy Ted Barron who coined the term ‘pseudo-documentary.’

Would this term apply to that movie starring Rip Torn as a psychiatrist?

Oh, Coming Apart by Milton Moses Ginsburg. That was one of the movies we watched in [Ted Barron’s] class. Because Rip Torn’s character is filming from a hidden camera perspective, you can’t help but wonder: who’s real and who’s not? It’s blending the line. It’s a fiction film that has elements of documentary. It’s not a mockumentary, [parodying documentaries in a transparent fashion]. They’re fake documentaries; pseudo-documentaries. They’re real movies that are made to look like documentaries and what that’s saying is, ‘hey, if we can fake this and make you think it is real, then what’s the difference between the two things?’ Look at a movie like David Holzman’s Diary. When it premiered, people were like, ‘oh my God, this is incredible. What a great documentary about this guy!’ And then then it turns out to be directed by Jim McBride and they’re all upset. They’re booing and throwing popcorn at the screen. They felt betrayed: ‘you took advantage of me, thinking I was watching a documentary!’

What do they expect to feel in a documentary versus a fiction film?

I don’t know. The thing is, I think that there is more forgiveness when people go into a documentary. I’ll give Lenny Cooke as an example. People go in expecting to learn something, but when they come out and they felt exactly what Lenny had gone through, it’s emotionally very powerful. They leave the theatre completely shocked and it’s the saddest thing they’ve ever seen, and it’s because they’re feeling what Lenny felt. They’re feeling that lost potential at a gut level, and they don’t always get to experience that in a documentary because they’re simply meant to be observing when watching a documentary. You’re not meant to be feeling things in that primal sense. But when you’re feeling at that level, it’s unnerving, and I think it’s very powerful. We could talk about this forever; it’s such an interesting topic. Hopefully the goal is that the distinction will disappear, and some things will just be based on the real and some things will just be based on the fake, and the fake comes from fiction or the fake comes from the real. Everything comes from the same place, so there shouldn’t be a distinction. And I think that the best documentaries being made today are the result of people just making movies, expressing themselves and expressing the views of the subjects, and that’s the best you can hope for. There are people that are fighting that fight, and I think it’s great.

Including you and Josh. So please keep doing it.

The pains of being The Caretaker: a video essay

November 5, 2015 § Leave a comment

Precious few horses remain as pleasurable to flog thirty-years-dead and bloated as they were when alive. One of these is The Shining, a film whose concurrent simplicity and opaqueness renders it eminently watchable, re-watchable and mysterious to the point of inspiring an insidious type of obsession. Having been subjected to decades of analytical dismemberment and identity-reassigning theories of the kind documented in Rodney Ascher’s documentary Room 237, Kubrick’s self-proclaimed ‘masterpiece of modern horror’ will once again find itself at the mercy of a personal ‘reading.’

Like a surfer who has just missed an elusive wave, this little piece may have benefited a touch from some Halloween momentum. Then again, that may have been an unnecessary pairing seeing as they – the video and the associated ‘personal reading’, that is – aren’t necessarily concerned with The Shining’s pedigree as a fear-mongering scare fest. Which is not to say that the aim is to reclaim The Shining from the horror genre and rebrand it as social commentary first and foremost. That being said…

…revisiting this picture on the back of a recent Blu-ray upgrade brought into sharper definition (pun intended) several elements that had hitherto gone relatively unnoticed: the significance of the term ‘caretaker’ in relation to Jack Torrance and his predecessor O’Grady, being white American males; the demographic statuses of the film’s three main protagonists, Danny, Wendy and Dick Hallorann (if Jack is the chief antagonist); the sly associating of American history, violence and privilege. Jack’s insecurity and seething resentment seemed – on this particular viewing – to stem from a place far beyond his failings as an aspiring writer. His was, is and will always be the rage of a failed son, a disappointing heir; a man all too aware of his being unable to live up to his birthright of supposed superiority.

Like most fanciful takes on the film The Shining, there may have been zero conscious intent on the part of the creators to comment on any of the above, but one can never be sure. Certainly not when a film seems to contain evidence for and against any theory or reading that one chooses to throw at it.

Share this: